Before I continue with more McNabbiana, I will drop in a short article on David Jones which I wrote for Mater Dei and which also appeared on Seattle Catholic. If McNabb speaks principally to my soul, Jones speaks principally to my 'cultural intellect', although he does not leave my heart untouched (Belloc very often speaks to my heart). Jones knew McNabb, although I think the artist (in many media) found the friar a little forbidding at times, and he had a number of disagreements with him (most notably over the Eucharistic theology of Maurice de la Taille SJ). It was the decidedly peculiar Eric Gill who brought them together. David Jones himself was not a straightforward man and has his own peculiarities, but he deserves great recognition for the strong Catholic focus of his writings in particular.

It is fascinating to consider that Jones served in the trenches at the Somme only a few miles away from where another Catholic author of note was serving, both imbibing the scene around them, subconsciously soaking up the terrible and glorious atmosphere of friendship and destruction, creating within them a hard kernel that would grow into the great fruits of their future works. The other writer to whom I refer is of course JRR Tolkien, and on many levels - if not stylistically - they have similarities as artists and deal with many of the same themes in their work - history, myth, culture, 'the long defeat'. Both of course loved the ancient Liturgies of the Church and were very greatly dismayed when the modernists dismantled them. I mean to write an essay on what unites them and what separates them but it has so far got no further than a dream.

Not many people know of David Jones. Even amongst those who should comprise part of his natural constituency – literate British Catholics – he is largely a forgotten man. Yet Jones, in his works, exemplifies much that was creative and insightful about the Church before Vatican II, the Church that so many neo-Catholics, fence-sitters and outright progressives now deride as sterile and mindless. Moreover, he simultaneously encapsulated many of the artistic and philosophical tensions of the twentieth century, which tensions were themselves bound up in the ‘long defeat’ that is Vatican II and its aftermath.

David Jones was born in 1895 in London. His father, also London born, was of Welsh Chapel up-bringing, his mother was English and Anglican. From an early age he showed great artistic potential and he was enrolled in Camberwell Art School at the tender age of sixteen. He joined up with the Royal Welch Fusiliers early in 1915, and spent the rest of that apocalyptic struggle in the trenches, except for two brief absences, one in late 1916 after suffering a wound at Mametz Wood in the aftermath of the dreadful Somme assaults, and one late in 1918, from trench fever, during the last desperate German offensive. He remained a private for the whole period. He was scarred by his experiences – a later history of nervous breakdowns could with ample justice be traced back to his war years – but they also influenced his art and later writings tremendously. A glimpse of Holy Mass offered by a priest in a barn not far from the Front Line was a significant factor in the process which led him after the war to become a Catholic. He was formally brought into the Church by Father O’Connor, GK Chesterton’s confessor, friend, and model for “Father Brown”. These years immediately following the 1918 Armistice were a period of great fruitfulness in conversions for the Church – D B Wyndham Lewis and J B Morton are just two other converts of this period who became great Catholic writers (and, in their case, also humorists – I feel another article coming on!).

Over the next fifteen years, his stock as an artist, engraver and illustrator of books rose immeasurably, until in his last years he was counted as one of the greatest living British artists, especially for his watercolours (Kenneth Clark, of Civilisation fame, thought him the greatest British watercolourist since Blake). At the beginning of this period he had fallen in with Eric Gill at Ditchling (where he learned engraving and calligraphy), met Father McNabb, fallen in love with Gill’s daughter, Petra, got engaged to her (it came to nothing), moved with Gill to Wales, and, returning to London, become a member of the influential “Seven and Five” group of modern artists (until he was “thrown out” for being behind the times). Today, his reputation still stands high enough for several of his works to be seen on the walls of the Tate (not that that is perhaps much of a clear commendation these days).

However, it is as a writer that his reputation – amongst those who have heard of him – still stands highest. He came late to writing. His first written work (which I think his best) was In Parenthesis, an epic prose-poem, semi-autobiographical, concerning the wartime experiences of Private John Ball, which ends (as did Jones’s first stretch of war service) in the battle for Mametz Wood. He wrote it before, during and after a series of nervous breakdowns which afflicted him during much of the 1930s. It was finally published in 1937 to great critical acclaim and won the only literary award then available, the Hawthornden Prize. TS Eliot wrote a preface for it and referred to it as “a work of genius”. For some years afterwards Jones struggled with a second book on his later war experiences, The Book of Balaam’s Ass which he never completed, finding those later war years impossible to set down without great anguish to himself, and without failing sufficiently to manifest their extraordinary mechanical horror and inhumanity. Eventually, in 1952, he published another long poem, The Anathemata, which effectively involves the whole historical sweep of Western European development, from the retreat of the glaciers through to modernity, hinging (obscurely) upon the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, and the Holy Mass. The Anathemata is probably considered his greatest work (W H Auden referred to it as “probably the finest long poem written in English this century”), although I am tempted to think that such a largely academic judgement has grown up principally upon account of the complexity and difficulty of that work. Academics have an especial liking for matters difficult to grasp and impatient of easy comprehension: a preference for arcane and complicated literary works can sometimes serve as shorthand for self-identifying the interested academic as particularly “deep” or “cerebral”. I find The Anathemata in part almost unreadable and seldom a pleasure to recite or read. Footnotes (Jones’s own) clutter it up and frequently threaten to swamp the page in abstruse reference. Other, shorter poems, came out later in Jones’s life, some broken off from his failed work, The Book of Balaam’s Ass, some separate and discrete endeavours: these can be found collected in The Sleeping Lord (1974). He was made a Companion of Honour early in 1974 and died, alone, in the Calvary Nursing Home in Harrow, in the Autumn of that year. He never married, and left no children

This biographical portrait does not do Jones justice. In particular, it does not do justice to the depth of his Faith, to the extent to which Holy Religion influenced, indeed formed and filled his ouevres, especially with regard to the written word. Jones was very interested and attached to the Catholic liturgy and he lamented the passing of the Old Mass. He was one the great and artistic good whose names were affixed to the letter to The Times of 6th July 1971, imploring the Catholic authorities, even if only on grounds of its unparalleled cultural merit, to retain the Old Rite. Just as his first exposure to the Catholic faith came from the Mass, witnessed through the crack of a barn door just a few hundred yards from the shell-cratered horrors of the Front Line, so the last poem he was working on was “The Kensington Mass”, dedicated to Fr O’Connor, an exploration of the ancient liturgy and its connection to Celtic and English myth and culture, which opens:

“clara voce dicit: OREMVS

et ascendens ad altare

dicit secreto: AVFER A NOBIS…

and in lowly accents

he says the rest

should you be elbow-close him

you may catch his

soft-breathed-out

PER CHRISTVM DOMINVM NOSTRVM”

Yet in truth, Jones, in his art, literature and in some of his opinions, is not someone with whom traditional Catholics will always agree or sympathise. In poetry he ranks alongside Pound and Eliot as a High Modernist (while that term is not to be confused with theological modernism there is an inescapable kinship between the two phenomena). Jones’s poetry does not rhyme and some will claim it isn’t really poetry at all, but dissonance and confusion. Belloc would have looked at it quite askance (as far as I know, it is not known what Belloc actually thought of Jones: Jones did however contribute an essay on The Myth of Arthur to a volume of essays celebrating Belloc’s seventieth birthday). As with all (artistic) modernism, Jones’s poetry is stylistically fractured and difficult to follow at times; it is highly personal and replete with quite arcane and obscure references to Celtic and Old English literature, history and myth, all inter-twined with parallel or analogous references to the Life of Christ, His Sacraments and the Faith. Like all Modernists he struggled in the post-War period with what he saw as the chasm that divided Edwardian England (Europe) and the modern age: unlike Pound, the new to him was strange and unfamiliar and he wanted to act as a pontifex, a builder of bridges between the old cultures and truths and the new bastard age. His style was the new style, reflecting the new environment (which he in part loathed: he detested the abasement of language and technological megalopolitan culture, so-called), but his content was the old high matter of Celtic and pre-modern England, of myths and old tales, of Christ and of the Faith.

David Jones attached great importance to the liturgy of the Church, not just as a practising Catholic but as a poet. When Jones became a Catholic, under the influence of Eric Gill he read Maritain’s Art et Scholastique (translated by Father O’Connor, interestingly enough) and developed a rich understanding of the Thomist definition of art, which he saw as intimately related to the meaning of sacrament. In a sacrament, something is effected, is made: the form of the sacrament symbolizes and effects that making. In art, the thing painted, written, sculpted, is likewise made: the effect of a piece of art is utterly bound up with how that piece of art has been written or drawn, with the words, their sound and meaning, with the paint, its colour and application. After Gill, Jones considered Man to be a natural maker, homo faber, and saw that art, sign-making and sacraments were all natural to him. All pagan religions had sacraments of a sort often foreshadowing the Sacraments proper of Holy Mother Church, of Christ.

Jones saw the Liturgy of the Mass as the most symbolically rich and developed of the rites surrounding a Sacrament, and the form and meaning of the immemorial Latin Rite gave life to much of his poetry, from The Anathemata, through early Mass poems such as Caillech and The Grail Mass through to the unfinished The Kensington Mass. The Liturgy was also important in Jones’s eyes because it helped “plug man into his past”, in a way which was becoming increasingly difficult in modern times. As he once wrote: “Quite apart from the truth or untruth of it [the theology of the Mass], only by becoming a Catholic can one establish continuity with Antiquity”. Jones became very anxious when he heard of plans to abolish the Old Rite, fearing “an unbridgeable discontinuity” in the one area – the Catholic religion – which still formed a bridge with Man’s past. (He has already lamented many of the earlier changes to the Church’s Holy Week Liturgy.) So much of what Man was could only be properly grasped in the light of his past, and since the Great War so little of that past, of history, of ancient literature and culture and myth, was still extant in the hearts and minds of Western Man save what the Church had, as in the post-Roman Dark Ages, sheltered from the barbaroi of modernity.

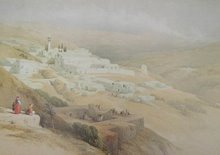

Jones spent some time in Jersusalem in the mid-30s, recuperating in the aftermath of one of the more severe of his nervous breakdowns. The sight of British soldiers patrolling the New Testament streets much as Roman auxiliaries had patrolled them at the time of Christ made a great impression on him. Empires, whether British or Roman, were never a source of joy to Jones (he agreed with St Augustine that empire was theft), but he acknowledged the signal part that the Roman Empire had unwittingly played in the establishment and development of the Catholic Church. The thought that Christ has died on the Cross, that momentous event, the very fulcrum of History, of human existence, witnessed by bored or baffled soldiers, servants of an Empire no less glorious, no less cosmopolitan, no less sure of itself than the British Empire already waning in his day, fascinated him. A great number of his poems, many incomplete and printed posthumously in The Roman Quarry, concern themselves with the Empire, and with often stunning anachronism place modern ideas or dialogue in a Roman setting to better illumine the ‘nowness’ of Christ’s Incarnation and Death and the sameness of so much of the modern that yet so foolishly despises the old. One poem deals with a conversation between a particularly cunning Judas and Caiphas. In another, The Fatigue, a Roman officer addresses his men, who, unbeknownst to them all, are going to set in motion the Passion of Christ by arresting the troublesome Galilean in the Garden of Gethsemane. In another poem, set at a Roman dinner party taking place during the events of Holy Week, with great dramatic irony guests discuss, in a flippant manner reminiscent of some 1920s London fling, the success of the Roman policy of religious toleration, the desperate fanaticism of Jewish sectaries, and the final, permanent victory of the Roman Way over superstitions and local religions.

All this may make Jones seem more a poet of ideas than of words.. He was, however, enormously gifted with words and could write as beautifully and movingly as he could arcanely or obscurely. Here, from In Parenthesis, he describes the night parade before his battalion moved down to the trenches for the first time:

“Cloud shielded her bright disc-rising yet her veiled influ-

ence illumined the texture of that place, her glistening on

the saturated fields; bat-night-gloom intersilvered where she

shone on the mist drift,

when they paraded

at the ending of the day, unrested

bodies, wearied from the morning,

troubled in their minds,

frail bodies loaded over much,

..‘prentices bearing this night the full panoply, the complex

..paraphernalia of their trade.”

He did indeed carry within him many of the tensions of the century in which he lived, but he lived – and died – a Catholic and his poetry is full-blooded in its Faith. Interestingly, Jones’s written works are enjoying something of a (comparative) revival: this is of course a two-edged sword. As many people may through his works catch some glimpses of the Truth as may attempt to veil that Truth with commentaries on Gender and Race in the poesis of David Jones or Jones: Man, Myth and the Marxist Dialectic. Still, he has not suffered from his Catholicism like some others, for example the great historian and historiographer (awful word) Christopher “Tiger” Dawson. For that at least we should be grateful.

[PRACTICAL ADVICE: If any reader should be inspired or browbeaten by this article into reading some Jones, I recommend, indeed ORDER, that you begin with In Parenthesis. I further recommend that you read a good portion of the beginning of the book aloud, at one sitting, with a good deep glass of red at your elbow, in order to build up the proper and necessary momentum. Finally, I suggest that you avoid reading about his works, as more than enough brain-numbing, over–complex commentary has been written about them to stifle the interest of even the most ardent enthusiast, but rather read them yourself without benefit of academic murk.]

No comments:

Post a Comment